Session 9: Gehry’s Soft Umbrella

- Sofía I. Capllonch

- May 1, 2022

- 3 min read

The study of architectural precedents as part of the design process is constantly reinforced in both professional and academic environments. Selecting and analyzing precedents is a practice that sets the past as a reference for what is about to be created, taking into careful consideration aspects to build upon or reinterpret entirely for the purpose of a project. While the importance of precedents cannot be denied, today’s technological advancements in drafting, model making, and architectural visualization propose newer, digital ways of idealizing design. Abiding by this fact, and as Greg Lynn suggests in his Embryological House, the form is able to harbor its own intrinsic conditions that comprise its diagrammatic necessity. Put simply, the originary conditions established by precedents would not necessarily be needed when algorithmic and parametric methods are used, as these same methods would provide a useful starting point; but what if both precedents and technologies could coexist? American architect Peter Eisenman analyzes Frank Gehry’s Peter B. Lewis Building as a case study for this argument.

In Ten Canonical Buildings, Eisenman equates precedents to disciplinary persistencies. Stating that “architecture may always look like architecture because it shelters, encloses, resists the forces of gravity, and is sited”, Eisenman implies that an existing knowledge of architectural history is a necessary component when developing a design idea. Lynn, however, arguments that the extensive study of precedents is not as relevant to the architecture of the future. If new times bring about new ways to visualize and develop design, it would be logical to rethink the starting point of a design, particularly in its early stages. For Lynn, the role of the digital is to undermine that of the analog, meaning the historical precedent.

While Lynn’s argument is justified, it is not an absolute truth, nor is it the only way to embrace emerging technologies in the design process. Frank Gehry uses computational processes in the creation of his characteristically amorphous sculptures, but it is precisely the sculptural aspect that adds a layer of personal expression to his work. In this way, and as Eisenman argues, Gehry’s ideas stemmed in the analogous and were later translated to the digital. Gehry also demonstrates an understanding of program and diagrammatic organization, meaning that precedents did, in fact, play a vital role in the project’s inception. In trying to further understand Gehry’s work as an architect, it may be useful to then see precedents and digital processes as two opposite, yet equally important, components: Gehry’s ideas are brought to life with the aid of algorithmic logics, while these same algorithmic processes are dependant on Gehry’s artistic expression and regard for precedents.

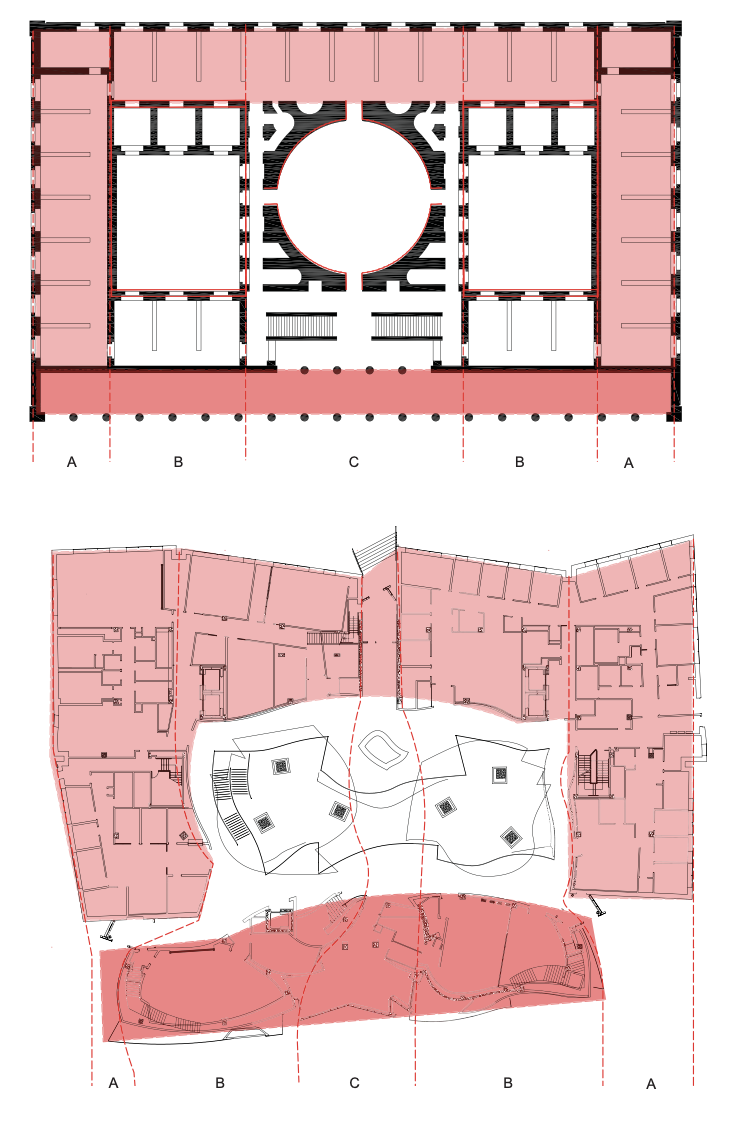

The Lewis Building for the Weatherhead School of Management uses Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s Altes Museum as a notable precedent in terms of plan. The diagrams shown in the chapter demonstrate a clear understanding of simmetries and programmatic functions plan-wise, but Gehry himself innovates and proposes his own way of using precedents. The Lewis Building becomes distorted in architectural sections, meaning that instead of a vertical extrusion, the building is literally sculpted from an original, orthogonal plan. The evolution from plan to section is not immediately evident from the project’s exterior; as like most of Gehry’s buildings, the Lewis building is covered by a “soft umbrella” which originated in the designer’s series of freehand, analogous sketches. From orthogonal plan to warped section, and from sketch to algorithmic models, Gehry leaps constantly from the analogous to the digital, demonstrating that architecture as a discipline can embrace innovation while respecting the past.

References:

Eisenman, Peter, Stan Allen, and Ariane Lourie. “The Soft Umbrella Diagram.” Essay. In Ten Canonical Buildings 1950-2000. New York: Rizzoli, 2008.

Comments